The Citizen’s Proposed National Water Law

In Mexico, a 2012 constitutional amendment recognised the human right to water, requiring a new national water law. Coordinadora Nacional Agua para Tod@s Agua para la Vida has proposed the citizens’ bill, which has been developed through a nation-wide bottom up process. It connects local grassroots struggles against privatisation, water resource contamination, indigenous peoples, and urban popular movements for access to, and local control over, water resources. Important local water struggles in Puebla, Guadalajara, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Ramos Arizpe, Saltillo and Mexico City are the background of this national mobilisation. The citizens’ bill ambitiously addresses sustainable water basin plans and democratic water service provision in an integrated way.

In contrast, the federal government’s proposed bill, developed behind closed doors, would strengthen executive authority over water, and would mandate the privatisation of municipal systems: it would promote energy-intensive hydraulic megaprojects and ensure water availability for mining and fracking. The citizens’ initiated National Process for Consensus on Water has managed to thwart three attempts to pass the goverment’s proposed bill fast-track, without debate.This article was written by the regional campaigners of the Coordinadora Nacional Agua para Tod@s : Gerardo Alatorre, Omar Arellano, David Barkin, Elena Burns, Rolando Cañas, Luis Rey Carrasco, Helena Cotler, Adriana Flores, Esther Galicia, Emilio García, Raquel Gutiérrez, Rossana Landa, Diana Luque, Alfredo Méndez Bahena, Rosa Isela Méndez Bahena, Leticia Merino, Rodrigo Migoya, Pedro Moctezuma, Ana Ortíz Monasterio, Úrsula Oswald, Ricardo Ovando, Luisa Paré, Francisco Peña, Raúl Pineda, Víctor Quintana, Gloria Tobón and Alejandro Velázquez.

The Citizen’s Proposed National Water Law

The Constitutional reform recognizing the human right to water in Mexico, approved on February 8, 2012, mandated a new National Water Law, to guarantee “equitable and sustainable access and use” of water, through the participation of citizens (unprecedented in the Constitution) together with the local, regional and national levels of government.

That same month, organizations 1 and researchers throughout the county initiated a broadly participatory process to write “the water law that Mexico needs”, and to build the strength required for its approval and enactment. This process has been structured and driven by the Coordinadora Nacional Agua para Tod@s, Agua para la Vida, a regional and national coordinating body which has been forged out of the process itself.

Our proposed water law establishes that water is a national commons, produced by Nature, and that the decisions regarding water must be made by Mexico’s citizens and peoples from the local to the national level. Our law would not permit any arrangement which would make water a commodity or would allow private control over, or the extraction of profits from any aspect of water management.

Our law is centered on community, citizen 2 and governmental co-management of watershed and municipal systems through legally binding plans, with citizen oversight to ensure governmental compliance. The participatory planning processes will seek to achieve a National Agenda for Water in 15 years: Quality water for all; water for ecosystems and for food sovereignty; an end to water contamination, to the destruction of watersheds and aquifers, and to avoidable vulnerability to droughts, floods and climate change in general.

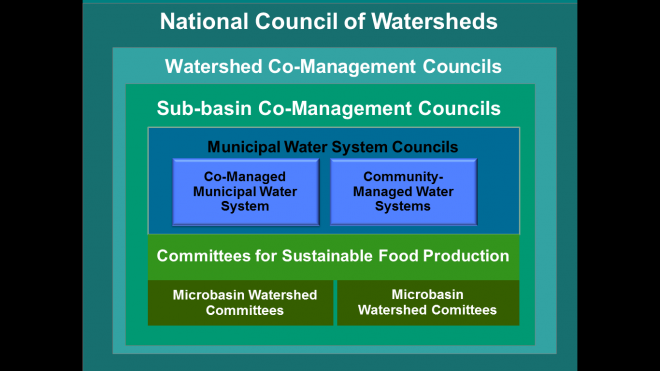

Our law defines two types of decision-making structures. For watershed planning and management, we propose Microbasin Committees, Sub-basin Commissions, Watershed Councils, as well as a National Council of Watersheds, with citizen and community representatives holding the majority of votes in each. The first, local microbasin level would be open to participation by all, and from there, spokespeople would be elected to participate on each successive scale to the national level, with the possibility of electing or inviting external specialists as needed. Representatives from governmental ministries of water, environment, forestry, health, agriculture, economy, urban development and civil protection would also participate in these councils.

The Watershed Councils would develop legally binding Watershed Master Plans, which would describe the actions required to achieve the goals of the National Agenda in that watershed, giving priority to local and upstream solutions. These Plans would define Areas of Importance (forests, recharge zones, wetlands, flood plains) in which land use would be severely restricted, and public funding would be available for restoration and management by local communities.

To overcome the current crisis of extremely excessive and concentrated water rights for non-essential uses, the Watershed Councils would also recommend the reassignment of superficial and groundwater rights to fulfill the Constitutionally mandated criteria of: equal and sustainable access; the fulfillment of the rights to water, food and a healthy environment, and indigenous peoples’ rights to preferential access to the waters in their lands,

Given that the rights to 77% of the country’s water have been assigned to agricultural users, primarily highly polluting agroexporters in the northern desert region of the country, each Watershed Council would have Committees for Food-and-Water Planning. These Committees would determine the infrastructure and actions required for achieving food sovereignty within the context of watershed restoration. Farmers would have to develop and follow transition plans towards agroecological practices in order to have access to irrigation water.

The National Council of Watersheds would propose the yearly federal budget for water to the Legislature, and would also name a short-list of three candidates for the President to choose from to preside over the National Water Commission (a cabinet-level position). The National Council of Watersheds would also have the right to review and question any international treaty which could affect water sovereignty or the human right to water in Mexico, prior to its signing.

In watersheds which suffer from subsidence and surface cracks due to aquifer overexploitation, chronic flooding, or neighborhoods without continuous access to quality water, their Councils could demand that their watersheds be declared Zones Under Extreme Water Stress. Under such decrees, new projects of profit-oriented urbanization could not be authorized until existing water crises were resolved.

For the planning and management of water and sanitation systems the Citizens’ Proposed Law would recognize and strengthen the role of community-run systems (commonly the sole source of water for indigenous, rural or poor urban communities). It also foresees the democratization of the Boards running municipal systems—which would be composed primarily of elected representatives from the various zones of the city, without the intervention of political parties, whose terms would be staggered in order to guarantee continuity.

A Municipal Board, composed of citizen representatives of the water systems and government representatives, would develop and carry out a Municipal Plan for the Right to Water and Sanitation, to guarantee the equal and sustainable access to water, primarily for personal domestic and public use. It would guarantee access to public drinking fountains and clean bathrooms, and would seek ways to make optimal use of rain and domestic and public waste water. This Board would oversee the transition to a zero discharge (100% recycling) policy for industrial users.

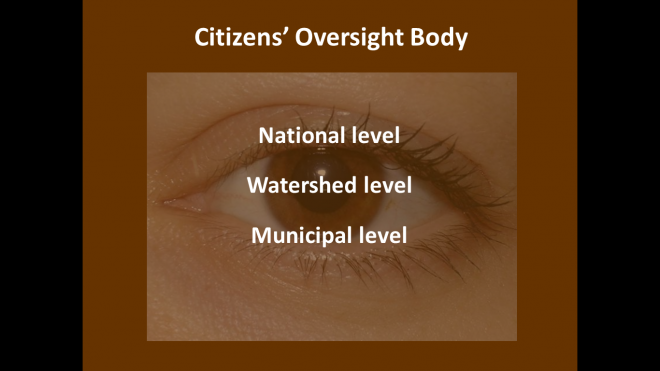

In order to eradicate corruption, Citizens’ Water “Contraloría” 3 Boards with official standing would be self-organized at the municipal, watershed and national levels. These bodies would work with a (proposed) Water Justice Procurement Agency, as well as with the Federal Auditing Authorities and the National Commission for Human Rights, to monitor whether government officials are ensuring the respect for the human right to water. These citizens’ bodies would produce recommendations, including, when needed, the request that a government official be removed from office. A publicly funded Legal Services for the Protection of Water and Environmental Rights would make it possible for citizens to sue government officials and companies.

The proposed water law would establish a National Fund for the Human Right to Water and Sanitation to guarantee direct access to public resources for self-organized projects in communities without access to these basic rights.Our law would prohibit access to the nation’s waters for toxic mining, toxic industries or fracking, or for the irrigation of lands where toxic agrochemicals are being applied.

The first version of our Citizens’ Water Law was presented to federal legislators from a diversity of political parties on 9 February 2015, with the express agreement that they would promote it as is, without submitting it to party dynamics. On February 23, it was presented in the Senate as a Citizens’ Initiative by 22 Senators from 4 parties.

We have been able to successfully block repeated attempts (2014, 2015, 2016) by the federal government to impose their own National Water Law, due in great part to the fact that we had come up with our own widely supported alternative. Their law would reduce the “human right to water” to 50 liters a day; it would mandate the privatization of municipal systems; it would promote the construction of (private) capital- and energy-intensive hydraulic megaprojects. “Strategic” activities such as mining, fracking and energy production, would have priority access to water, and the rights of indigenous peoples to water would be erased. It would allow the “water authorities” to make direct use of force; polluting industries would “self-police”; and huge fines would be levied against anyone installing water research or monitoring equipment without prior governmental approval.

In order to continue to improve and gain ever greater support for the Citizens’ Water Law, on November 3 and 4 2015, Agua para Tod@s initiated a National Process of Consensus-Building for Water, for which Thematic Working Forums are being held in 27 universities around the country. In August, a National Forum will review the proposals generated by these forums, to produce an improved version of the Citizens’ Water Law.

Meanwhile, we are organizing Local Water Committees among communities whose right to water is not being respected. We work to defend and strengthen community water management systems, and to further the rights of workers in municipal water systems. We are promoting bottom-up processes for watershed co-management, wherever conditions will permit. We are drawing up watershed management plans and carrying out community projects, including rainwater catchment, reforestation, maintenance of streams and canals, water treatment plants, water quality monitoring.

In the midst of an adverse environment, together with other organizations, we are questioning expensive and damaging megaprojects, as well as toxic mining and fracking; we seek to end the opacity and promote public debate regarding the policies that the World Bank and other institutions are promoting in Mexico. We are struggling for alternatives to the privatization of municipal systems and we are speaking out against the violence which is being exercised against those who are defending their lands, waters and other commons. Through actions involving the courts and human rights bodies, forums, marches, caravans and presence in the public and social media, we are seeking to eliminate and overcome corruption and external intervention in the water sector.

Together we have been discovering how water in Mexico should be governed, and we are building the capacities, the legitimacy and the organizing strength to make it happen.

More information

@AguaparaTodxsMX

This article was written collectively by : Gerardo Alatorre, Omar Arellano, David Barkin, Elena Burns, Rolando Cañas, Luis Rey Carrasco, Helena Cotler, Adriana Flores, Esther Galicia, Emilio García, Raquel Gutiérrez, Rossana Landa, Diana Luque, Alfredo Méndez Bahena, Rosa Isela Méndez Bahena, Leticia Merino, Rodrigo Migoya, Pedro Moctezuma, Ana Ortíz Monasterio, Úrsula Oswald, Ricardo Ovando, Luisa Paré, Francisco Peña, Raúl Pineda, Víctor Quintana, Gloria Tobón and Alejandro Velázquez

notes:

1. The process involves indigenous peoples’, water users’, municipal workers’, urban poor peoples’, and human rights organizations, as well as community-run urban and agricultural water systems, and organizations fighting water privatization, toxic mining and toxic farming, dams and fracking.

2. The Mexican Constitution recognizes the collective rights of original peoples (Art. 2), of ejidal communal landholders (Art. 27) as well as citizens’ rights (Art. 4) to participate in water-related decision-making. Therefore both this article and the Citizens’ Proposed Water Law refer consistently to “communities and citizens” as valid actors in watershed and water system decision-making and management.

3. “Contraloría” refers to an organism which exercizes oversight, “watchdog”, auditing and other fairness and anti-corruption functions.