Nestlé plan to take 1.1m gallons of water a day from natural springs sparks outcry

Opponents fighting to stop the project say the fragile river cannot sustain such a large draw

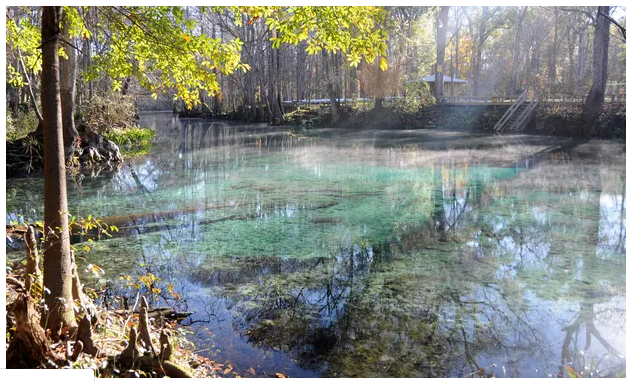

The crystal blue waters of Ginnie Springs have long been treasured among the string of pearls that line Florida’s picturesque Santa Fe River, a playground for water sports enthusiasts and an ecologically critical haven for the numerous species of turtles that nest on its banks.

Soon, however, it is feared there could be substantially less water flowing through, if a plan by the food and beverage giant Nestlé wins approval.

In a controversial move that has outraged environmentalists and also raised questions with authorities responsible for the health and vitality of the river, the company is seeking permission to take more than 1.1m gallons a day from the natural springs to sell back to the public as bottled water.

Opponents say the fragile river, which is already officially deemed to be “in recovery” by the Suwannee River water management district after years of earlier overpumping, cannot sustain such a large draw – a claim Nestlé vehemently denies. Critics are fighting to stop the project as environmentally harmful and against the public interest.

Meanwhile, Nestlé, which produces its popular Zephyrhills and Pure Life brands with water extracted from similar natural springs in Florida, has spent millions of dollars this year buying and upgrading a water bottling plant at nearby High Springs in expectation of permission being granted.

The company needs the Suwannee River water management district to renew an expired water use permit held by a local company, Seven Springs, from which it plans to buy the water at undisclosed cost. Nestlé insists spring water is a rapidly renewable resource and promises a “robust” management plan in partnership with its local agents for long-term sustainability of its water sources.

Yet company officials concede in letters to water managers supporting the permit request that its plans would result in four times more water being taken daily than Seven Springs’ previously recorded high of 0.26m gallons for its customers before Nestlé.

“The facility is in process of adding bottling capacity and expects significant increase in production volumes equal to the requested annual average daily withdrawal volume of approximately 1.152m gallons,” George Ring, natural resources manager for Nestlé Waters North America, wrote in a June letter to the Suwannee district engineers.

Campaigners against Nestlé’s plan, who have set up an online forum and petition and submitted dozens of letters of opposition ahead of a decision that could come as early as November, say that environmental grounds alone should be enough to disqualify the plan.

“The question is how much harm is it going to cause the spring, what kind of change is going to be made in that water system?” said Merrillee Malwitz-Jipson, a director of the not-for-profit Our Santa Fe River.

“The Santa Fe River is already in decline [and] there’s not enough water coming out of the aquifer itself to recharge these lovely, amazing springs that are iconic and culturally valued and important for natural systems and habitats.

“It’s impossible to withdraw millions of gallons of water and not have an impact. If you take any amount of water out of a glass you will always have less.”

Additionally, Malwitz-Jipson said, the Santa Fe River and its associated spring habitats are home to 11 native turtle species and four non-native species, which rely on a vigorous water flow and river levels.

“Few places on Earth have as many turtle species living together and about a quarter of all North American freshwater turtle species inhabit this small river system. A big threat to this diversity is habitat degradation, which will happen with reduced flows.”

Stefani Weeks, program engineer with the Suwannee River water management district, said that because Seven Springs was seeking a five-year renewal of an existing permit instead of making a new application. Board members could not consider in their final decision the Santa Fe River’s protected designation and a recovery strategy implemented in 2014 to restore reduced water flows and levels.

But the district has its own questions, and wrote to Seven Springs in July for a second time to request answers. “Their first response we didn’t feel was complete, so we asked for them to go into more detail,” she said. “Once they respond we will review that information.”

Among the items the district wants are an evaluation report of any harm that the project might cause to wetlands, and a documented impact study of Ginnie Springs. The permit cannot be granted, the district says, unless Seven Springs can show that there would be no change in “water levels or flows of the source spring from the normal rate and range of function” and “no adverse impacts to water quality, vegetation or animal population”.

Nestlé is no stranger to controversy over its water extraction activities. In 2017, the state water resources control board of California issued a report of investigation concluding that the company appeared to be diverting water “without a valid basis of right” from Strawberry Canyon in the San Bernardino national forest for use in its Arrowhead brand of bottled water.

Nestlé continues to dispute the finding and is still pumping water there – 45m gallons last year, according to published reports. But in the tussle over whether the company had historic rights to all the water it was taking from the creek, groups including the Center for Biological Diversity, Sierra Club, the League of Women Voters and the Save Our Forest Association were critical of Nestlé and its operations.

In a written statement Nestlé, which employs 800 people in Florida, said it wanted to address “misconceptions” about its plans.

“We adhere to all relevant regulatory and state standards. Just like all the previous owners of the High Springs factory which manufactured bottled water and other beverages, we are not taking water from a publicly owned source. Instead we are buying water from a private company which holds the valid water use permit,” spokesman Adam Gaber said, adding that Nestlé’s water use “will always remain strictly within the limit set by the permit”.

He said that Nestlé was also a responsible steward of the environment. “Our business depends on the quality and sustainability of the water we are collecting,” he said.

“It would make no sense to invest millions of dollars into local operations just to deplete the natural resources on which our business relies. It would undermine the success of our business and go against every value we hold as people and as a company.”

Fuente: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/aug/26/nestle-suwannee-river-ginnie-springs-plan-permit